The problem: Most organizations feel pressure to “add AI into their product,” and the fastest way to show progress is a chatbot. But chat is a UI choice, not a strategy. The problem is that chat makes a promise the underlying system often can’t keep. When teams jump straight into conversational interfaces, they often create user expectations the underlying system can’t support.

Why it matters: A durable AI strategy starts by defining the behavior of your AI—how it should understand user intent, how much agency it should have, and how present or human-like it should feel. The interface comes last.

Key takeaways:

- Chat can be the right answer, but only when it matches the task, the context, and the user’s expectations.

- Every organization’s AI approach should be different because their users, jobs-to-be-done, and risk profile differ.

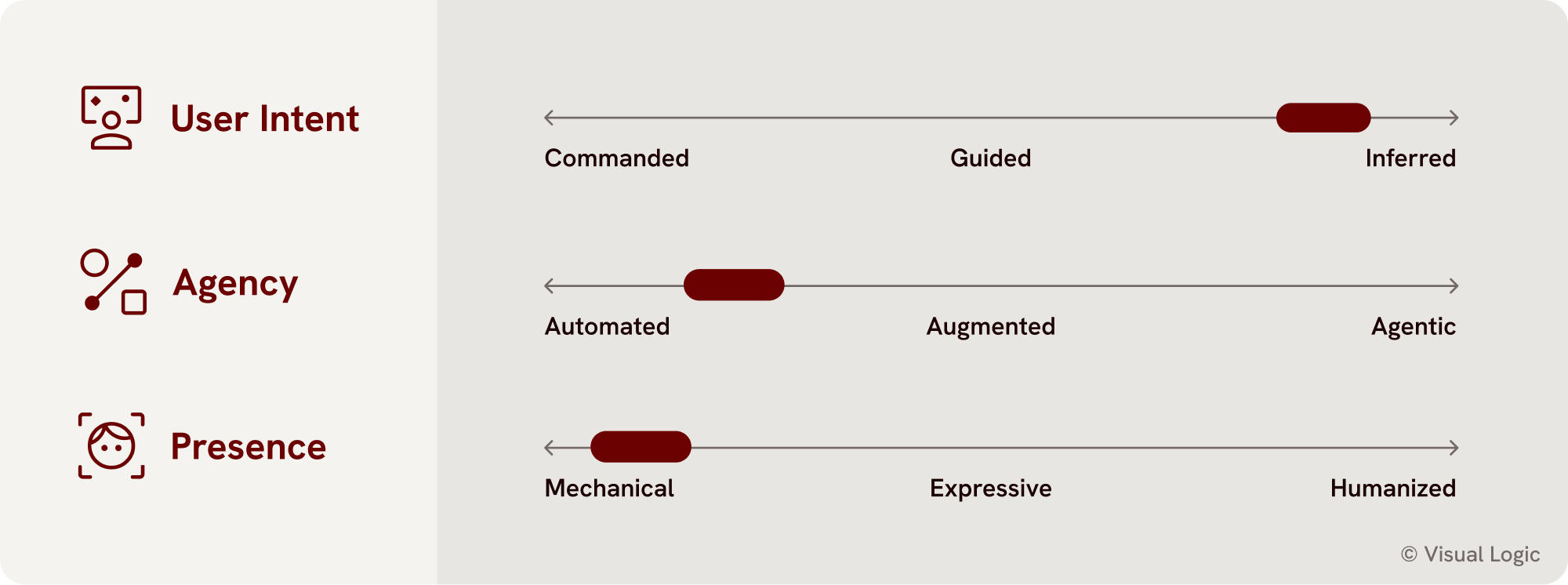

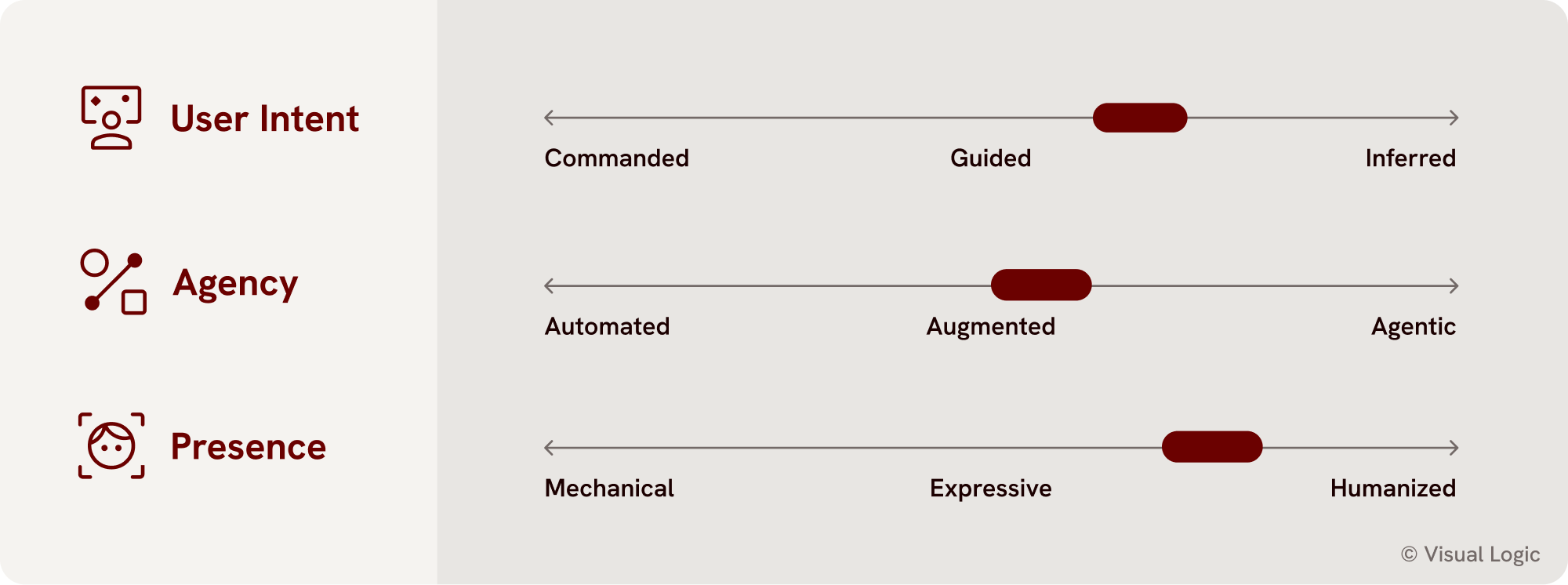

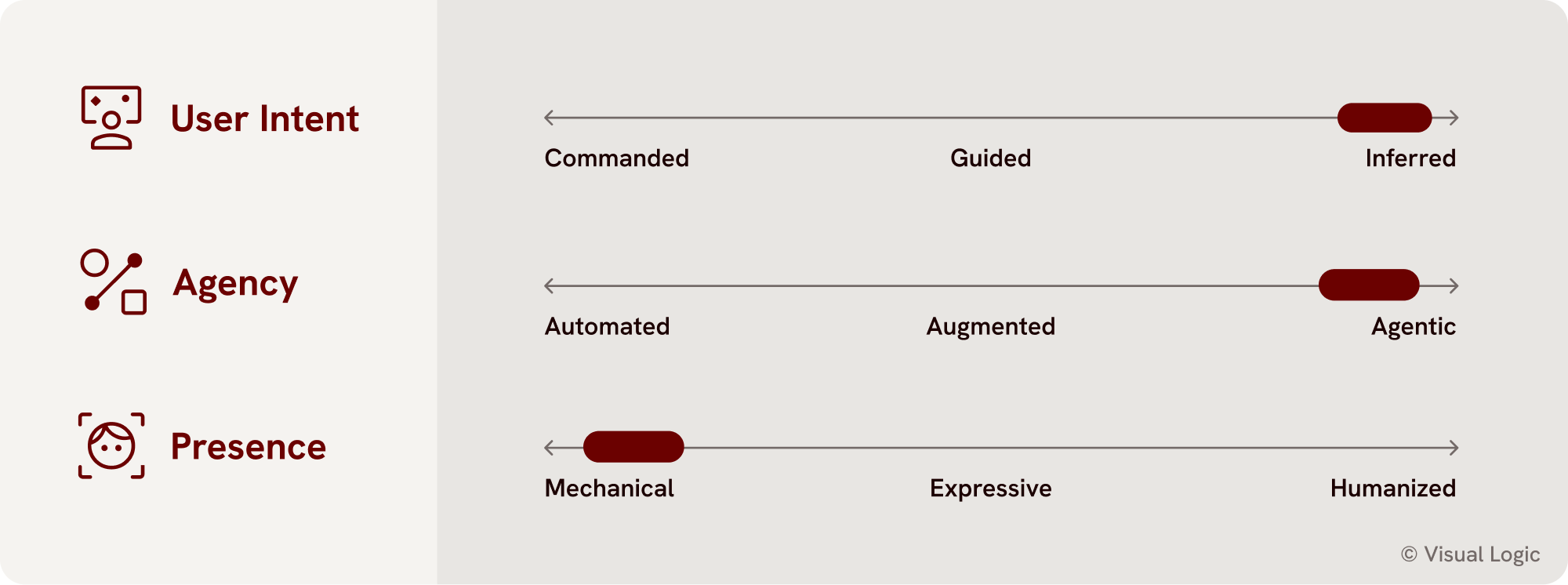

- AI product strategy is shaped by three levers: User Intent, Agency, and Presence.

- Over-indexing on any single lever (especially presence/humanization) creates trust problems and fragmented experiences.

- The companies who win with AI won’t be the ones who add the most chatbots, they’ll be the ones who redesign how their products understand human intent.

🎧 Listen to the Humans First episode to hear the whole conversation.

Why companies need an AI strategy before building AI into their products

As AI has gained rapid traction, teams have felt pressure from every direction—boards, competitors, customers, even Wall Street—to demonstrate that their product is “doing AI.” Chat interfaces became the fastest path to showing something tangible, and the industry followed.

The problem is that the visible solution is not always the appropriate solution. Chat feels powerful. It demos well. It feels like the future. But in most enterprise products:

- Users don’t want open-ended conversation

- The domain is too narrow for natural language to be reliable

- The cognitive load of typing a prompt is higher than clicking a button

- Chatting and reading long responses is not the most efficient way to work.

- Expectations quickly exceed capability

The result? Products that “have AI” but don’t feel intelligent, or worse, don’t feel trustworthy.

A well-planned AI strategy prevents that. And that strategy comes down to three decisions, or levers, that shape how AI should behave inside your product ecosystem.

The three levers to guide your AI strategy

Using User Intent, Autonomy, and Presence as a guide, your team can define what your AI is, how it behaves, and how people will judge it. Once those decisions are made, the UI choices will follow.

1. User Intent: How does your product understand what users want?

(Based on Jakob Nielsen’s Noncommand User Interfaces, with updated terminology for clarity.)

For decades, computing has required explicit commands: click, tap, type, select. AI breaks that paradigm. It lets products infer intent, sometimes better than users can articulate it.

User intent sits on a spectrum:

Commanded (low intent understanding, the user explicitly tells the system what to do)

In a commanded interaction, the user provides exact instructions and the system executes them. Predictable, but rigid. And if using natural language to command the system, it’s often more cognitively taxing than it needs to be.

This is where most software still sits today. It works, but it requires the user to translate their goal into the system’s vocabulary. It’s a world of exact commands rather than understood intentions.

Guided (mid intent understanding, users describe the outcome, not the steps)

Here, the user still initiates, but they don’t need to articulate every step. They simply describe what they want, and the system figures out how to get there. It’s the difference between saying “resize this image to 1080x720 and adjust exposure by 20%” versus “make this brighter and ready for a slide.”

This mode powers most conversational AI today, whether it’s drafting a kickoff plan, generating a cover image, summarizing a legal doc, or providing three options for a title. The user sets the destination; the system charts the route.

When guided intent works, it feels like collaboration. When it doesn’t, the user ends up re-explaining themselves, like giving directions to someone who keeps missing every turn.

Inferred (high intent understanding, the system anticipates needs without being told)

Think about how effortless it feels when:

- A Tesla turns itself off when you walk away.

- Apple Mail highlights two urgent emails at the top without you enabling anything.

- The Photos app outlines the subject you tapped and knows you probably want to extract it.

- Netflix lines up shows that hit your taste exactly, without a single prompt.

- A smart thermostat knows when your house tends to be empty and adjusts accordingly.

In all these examples, the intelligence is identifying the need without conscious effort from the user. Inferred intent experiences are quiet. Invisible. Helpful. They don’t need a personality to feel intelligent, they just need to be right. And for many products, this is where the biggest strategic upside lives.

2. Agency: How much autonomy should AI have?

(Based on the AI Fluency Framework by Dr. Mimi Onuoha and Dr. Nigel Cross.)

Agency determines how much power you give the system and how much control the user feels they’re giving up. The stakes are emotional as much as functional.

Automated (low agency, the system executes a fixed task)

This is the safe zone—rules, workflow steps, structured actions. Think: “Sort my inbox by unread,” or “Generate this report every Monday.” Most enterprise AI lives here today, and with good reason: predictability builds trust.

Augmented (mid agency, the system collaborates with the human)

This is the chat middle ground: the user asks, the system responds, the user corrects. It’s a back-and-forth. A negotiation. This looks like writing tasks, interpreting data, summarizing documents, or vibe coding. When done well, augmentation feels empowering.

When done poorly, it feels like babysitting a toddler who insists they can carry the groceries but drops half the bags on the sidewalk.

Agentic (high agency, the system acts independently)

This is where things get complicated, as the system acts independently on the user’s behalf. It’s where psychological discomfort kicks in.

We once worked on a project around an automated excavator that could scoop a perfect bucket of rock every time with a single button press. Not because it didn’t work but because the act of scooping was their craft—a signal of expertise. Full automation felt like identity loss.

We see the same pattern elsewhere:

- Skepticism about AI purchasing flights

- Hesitation to trust autonomous financial decisions

- Disdain for AI-generated art or music

Agency magnifies both the power and the emotional stakes of AI. It can save enormous time, but only when the user believes it’s safe to give it the wheel. Even then, AI can and will make mistakes, so it’s important to be cautious in applying agency to this degree.

3. Presence: How does AI present itself?

Presence is about how visible your AI is, and in what form. It includes the degree of anthropomorphism (assigning human traits to non-human systems), but broadens it to account for subtle cues: icons, animations, naming, tone, and personality.

Presence sits on a spectrum:

Mechanical (low presence, no anthropomorphism)

This is AI as infrastructure. Quiet, invisible, unbranded, unpersonalized. The intelligence feels like a natural extension of the product, not a character inside the product.

This is where Apple Intelligence is placing its bets. Apple has allowed Siri to fade into the background and shifted focus toward contextual intelligence: highlighting important emails, suggesting edits, extracting subjects from photos. Users get the benefit without feeling like they’re interacting with a personality.

Mechanical presence sets low expectations. It signals:

Don’t talk to me, I’m just here to help.

Expressive (mid presence, aesthetic cues)

Here, AI is visible but not human. We have often seen this portrayed as “magic” sparkle icons, rainbows, glowing, or magic wands. It could be certain animations to show “thinking” or “listening”. The user knows intelligence is happening, but the product isn’t pretending to be a person.

Tools like Google Docs and modern design platforms use this middle ground. Users know intelligence is present, but there’s no illusion of emotion or human-level understanding.

Expressive presence is emotionally friendly but leans “mystical” enough that, if overdone, it risks overpromising. The more magical the flourish, the more users assume something powerful must be behind it.

Humanized (high presence, anthropomorphism)

At the far-right end, the AI has a name, tone, or personality. It speaks conversationally. It feels like a companion. This is where expectations skyrocket.

Think about Alexa. In the early days, people genuinely talked about Amazon’s “smart” assistant as if she were a guest in their house. She had a voice, an identity, and a presence. But as users ran into the limits of what Alexa could understand, the expectations she set became liabilities. She wasn’t a human-like assistant. She was speech recognition wrapped in a personality costume. The mismatch eroded trust and created more frustration for customers, because their expectation was a human.

Products like Claude or highly personalized Notion agents with hats and sunglasses lean into this humanized presence intentionally, and because they offer broader context and reasoning, it works more often than not. But narrow-domain enterprise products rarely benefit from this approach.

Humanized presence isn’t wrong. It just must be proportionate to real capability.

How these levers interact—and why balance matters

Most organizations over-index on one lever: Presence, specifically, humanized presence. Not because it’s good UX, but because it’s the clearest signal that “we’re doing AI.”

But presence is only one lever. Humanized AI without real capability collapses trust. High-agency AI without intent understanding feels unsafe. And even strong intent modeling can fall flat if the surrounding experience doesn’t match the intelligence the user expects.

Balanced strategy is what creates differentiation.

But when you zoom out, different companies show how intentional positioning across the levers creates a signature AI feel:

Apple: High User Intent, Low Agency, Low Presence

Apple’s recent moves are subtle but powerful. They dodged the “Siri arms race” and instead leaned into intelligence that simply helps you live your life: surfacing an important email, extracting a subject from a photo, reminding you of your dad’s birthday with a video montage.

Wall Street hated it, because it wasn’t showy. But users feel the benefit because it reduces their cognitive load instead of performing for them.

Anthropic (Claude): High User Intent, Mid Agency, High Presence

Anthropic leans directly into the persona dimension: the product is named Claude. It speaks warmly. It feels present. But they deliberately pair that human-like layer with structured guardrails and reasoning transparency so the persona doesn’t outpace the trust.

Nest Learning Thermostat: High User Intent, High Agency, Low Presence

Nest doesn’t present itself as a persona. But its intelligence is deeply agentic: adjusting temperature, learning schedules, and acting autonomously. It infers patterns and takes action with almost no visibility—a great example of high agency paired with low presence.

Balance makes or breaks your AI product experience

The lesson isn’t “anthropomorphism is bad” or “chat is wrong.” It’s that AI strategy is the art of matching expectations with reality. Every lever has value. Every lever has risk. You win when they work together.

This isn’t new. It’s how we’ve always practiced design. We just can’t lose sight of that in a new landscape.

What this means for leaders building AI into products

An AI strategy is not a roadmap of features. It’s a choice about how your product should behave and how your users should feel when they interact with intelligence. Where are you implementing AI because of pressure, and where could you intentionally differentiate across user intent, agency, and presence?

A simple place to start: map your current product suite against the three levers. Where do products feel misaligned? Where does intelligence feel over-promised or under-delivered? These gaps are often where trust in your brand is quietly eroding.

Once you spot the inconsistencies, work through the framework to decide how you want your customers to interact with intelligence, and align your teams around that.

We help teams every day define their AI product strategy and align their organizations to design intelligent features in ways that foster trust and differentiation.